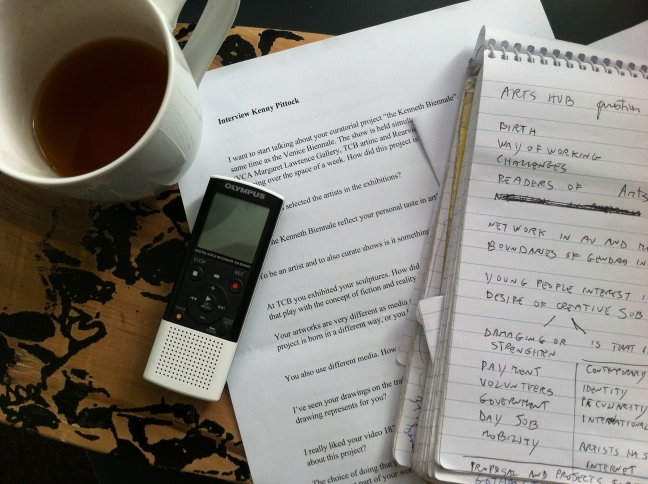

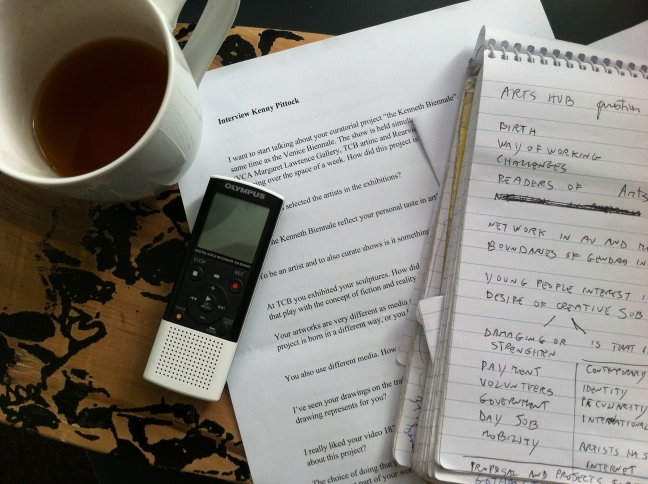

I just came back from my 32nd interview for my reportage in Australia, so I finally feel like I can tell my opinion about how to interview an artist.

The first thing you have to do is obviously contact the artist and you usually do that through her/his mail on her/his personal website.

The first mail has to be a quite formal style, without exaggerating though.

You have to be short and clear, explaining the artist why you want to interview her/ him and what aspects of her/his work are you interested in.

If your interview is part of a bigger project, like a reportage, spend a few words to inform the artist about it.

Don’t forget to explain her/him if this is your own project or if you are working for a magazine.

In this last case it would be nice to put a link to the website of your magazine, so the artist can have a look.

Put also your own website or blog in the signature, along with your personal page on a web magazine that hosts your work, if you have one.

That would give you credibility and would also give the artist the possibility to take a peek at your style and at the kind of articles you usually write.

The next mails would probably me more informal. At this point you can get rid of all the links in your signature, the “best” and “regards” and sign with just your given name.

In your second mail you can suggest the artist a place where you can have the interview.

The most common places are the artist’s studio, a nice and quite café, the space where the artist has currently a show or the gallery that represents him.

Give options to the artist. To meet her/him in his studio would be ideal – you can guess much more from the artist’s natural habitat than from outcomes of a simple conversation.

Of course, you can suggest to meet in the studio, but not all the artists have one and not everyone is happy to let a suspicious journalist or art critic in. If the artist tells you that his studio is empty or messy at moment, just don’t bother. Above all don’t insist.

If you are doing the interview in your own city, you probably would know the most quiet and suitable cafe for an interview. If you are abroad don’t be shy, just ask the artist if he knows a nice cafe to meet.

The choice would probably tell you something about the artist lifestyle and tastes.

In any case discover new places in a new city is always exciting.

Read More