THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 18

Brother Cane and the Josef Ng Affair

Given the big scandal his case provoked, you would imagine Josef Ng holding resentment to his country Singapore in one way or another. This is not at all the case. After two decades of auto-exile, working as a curator in Bangkok and Shanghai as gallery director, in December 2015 the artist and curator went back to Singapore, hired by the gallery Pearl Lam. As a young man, Josef was part of the Artist Village. It was a time when, as we saw earlier, there was almost no funding for art, and artists were making art for their own pleasure, with a particular focus on performance. Over time, the performers started carving some space for self-expression, and became bolder and bolder, eliciting some reactions. A pioneer of subversion in Singapore was Vincent Leow, who made an operation à la Manzoni, without even knowing of the precent, bottling his urine.

However strange all of those performances looked for the Singaporean public at the time (and I suspect even today), the real deal happened during the performance “Brother Cane” by Josef Ng in 1994, at Parkway Parade. The performance was conceived as a protest against the arrest and caning of twelve homosexual men, and consisted of caning slabs of tofu. Then the artist turned his back to the audience and snipped off some pubic hair. Here is the recollection of Professor of Live Art and Performance Studies Ray Langenbach:

Ng, dressed in a long black robe and black briefs, carefully laid out 12 tiles on the floor in a semi-circle. He placed the news cutting, “12 Men Nabbed in Anti-Gay Operation at Tanking Rhu” from the Straits Times on each tile. He then carefully placed a block of tofu on each tile along with a small plastic bag of red dye.

Duration 1 minute: Ng crouched behind one tile and read random words from the news cutting.

Duration 5 minutes: Ng picked up three strips of a child’s rotan tied into one piece. Striking the floor with it rhythmically, he performed a dance, swaying and leaping from side to side, and finally ending in a low crouching posture.

Duration 3 minutes: Ng approached the tofu blocks, tapping the rotan rhythmically on the floor and performed a dance. He tapped twice next to each block, then whipped each of the twelve bags of red dye and tofu on the third swing. Red paint and soft white tofu splattered violently.

Duration 1 minute: Ng said that he had heard that clipping hair could be a form of silent protest, and walked to the far end of the gallery space. Facing the wall with his back to the audience, he took off his robe, lowered his briefs just below the top of his buttocks and carried out an action that the audience could not see. He returned to the performance space and scattered a small amount of hair on the centre tile.

Duration 1 minute: Ng asked for a cigarette from the audience. He was given one. He lit it. He smoked a few puffs, then, saying “Sometimes silent protest is not enough,” he stubbed out the cigarette on his arm. He said “Thank you,” and put his robe back on.

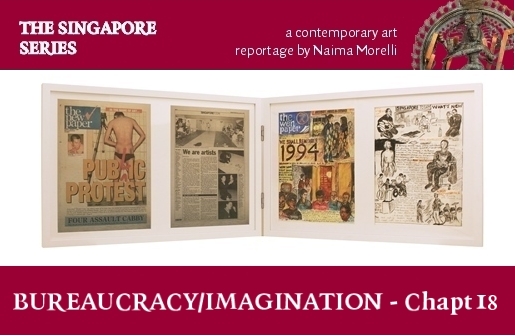

While this description sounds pretty harmless, the media didn’t see it in the same way. The morning after, Singaporeans picking up their magazines would find in the stands a copy of the “New Paper” with a figure giving the shoulder and a half-bared butt, with the titillating title “Pub(l)ic Protest”. It was not the only newspaper to put Josef’s buttocks on the front cover. As something happens to contemporary art, otherwise neglected, the scandal bounced all around the media, causing a great humming. Even if there was no complete nudity involved, Josef Ng was charged with committing an obscene act and banned from performing in public, and his theatre group’s grants were cancelled.

In the Singaporean art world narrative, this episode is described as a trauma for an entire generation of artists. While a newborn scene of creatives had just started experimenting and testing the boundaries, it was suddenly shut down. The second half of the nineties and the first part of the 2000s is a period considered as art repression. The “ban” was lifted in 2004. I put it in quotation marks, because it was actually a suspension of funding. This is an impractical thing that many other artists in the world face, working in the absence of funding. In fact, the real ban there was psychological. It was showing what would await you if you dare to push it too far: public exposure. Shame. And even if today the trauma has been overcome by a new generation of artists who haven’t experience it and know “how to behave”, a form of censorship is still there. It is not comparable to the real threat faced by artists in the neighbouring Southeast Asian countries like Cambodia or Vietnam, but it is present, if subtler. The way censorship works today in Singapore is described as punitive and preventive, politically involved and motivated. It can be direct, aka Legislation passed by parliament which restricts freedom of expression. The depute body is the CRC, the censorship review committee, appointed in September 2009 and headed by Goh Yew Lin, which reviews regulatory policies and standards across media to meet long term interests within society. In the case of performance art, the way censorship operates today involves occasional modifications and restrictions. But again, the real censorship in contemporary Singapore is not initiated by the government, but is on the part of the creators themselves.

Self-censorship and a culture of fear

“Did you hear the news about this huge mega-church which was preaching about giving away your money to them?” asked Eugene Soh, sitting in front of his computer in his room, surrounded by his photographic work and a lot of electronic equipment. “It’s an Evangelical Church,” he continued. “Their practice is to get their members to recruit more members and every member has to pay 10% of their income – even students – to the church building fund. Then the leaders use the church building fund for themselves, for funding their own lifestyle. They have now all been convicted. The judge said that in the culture of the church, they also created this atmosphere of fear, which is just what Singapore is doing to the rest of the people when someone speaks up and says, “hey, what happened to the money that I gave you? Did you use it for something else?” Then they would sue that guy and shut them down. This is what the church did to that one church member. “Hey, don’t you have enough money for the building already, why are you asking or more? Are you using it for something else?” Then he got shut down. They built a micro-Singapore culture within the church. And then a judge said something like, “You are building a culture of taboo and fear.” I said “Wah lau! The judge said that?!” He’s indirectly talking about Singapore. Like… woo! So we are becoming more aware that Singapore is like that. I guess there will be more outspoken things.”

I was talking with Eugene about the clean look and harmless ethos of a lot of the art which has been produced in the Lion City, and the artist pointed out that Singaporean art is very clean, precisely because of the specific culture he lives in: “Singapore has a really unique way of working. You can’t say certain things about Singapore, you can’t talk about religion. There are a lot of things you can’t say and you’d self-censor. But even if you say them, the police won’t come and catch you, the other Singapore citizens they would come and put you down. We would censor ourselves. This is the culture in Singapore. You don’t talk of certain things.”

I asked him if in his opinion and experience, artists would like to talk about some of these issues they are discouraged to express. He said he thinks artists would be open to talk about some of these issues, but they grow up in this society, so self-censorship comes naturally. It becomes second nature.

Brother Cane: performance art as a way for the community to adjust to change and trauma

After his comeback in 2017 for Pearl Lam, Josef Ng spoke out about the infamous episode in one interview for the Today magazine, called “Brother Cane is part of me”: Josef Ng opens up about past controversies and future hopes”. The artists pointed out that, while in general he was not afraid to talk to the media, in Singapore he felt he needed to be cautious: “There have been so many miscommunications about my performance and the after-effects, what I did and what I’ve been doing ever since.” After the controversy surrounding his performance, Ng kept in touch with fellow artists but stayed away from the art scene. “There was such a loud reverberation in the aftermath and I personally didn’t want to deal with it,” he admitted. “I stepped out of art completely, just to assess whether it was something I really wanted to do for my whole life.”

In the essay “Looking back at Brother Cane: Performance and State of Performance” in the important book “Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art”, Ray Langenbach speaks of performance art as a way for the community to adjust to change and trauma. This can happen with a conservative modality or with a disruptive modality. The reference in the text was precisely to Ng’s performance, that was responding to trauma with a disrupting action of protest – though not intended to be the big scandal it resulted in.

One can argue that this re-presentation of the re-presentation started with the re-elaboration of the performance treatment and the subsequent “ban” by many artists who measured themselves with the topic. In the “Culinary history of Singapore”, artist Lina Adam, president of what remains of the Artist Village at the time I’m writing, reinterpreted the main moment of the history of contemporary art in Singapore through food. As she put it, “fine ingredients have been selected from the history of performance art in Singapore.” In the process, she paid attention to how the works of art, especially performances, are rarely documented accurately. Lina made her selection of ingredients using information gained from her own recollections, word of mouth, conversations with friends and acquaintances, online research and private collections of catalogues, books and photographs. The ten-course degustation menu was accompanied by a PowerPoint presentation detailing the history of the ingredients and the references to the history of performance art in Singapore over more than twenty years. And of course, the tofu served as a reminder of the Josef Ng affair.

Lee Wen also produced a piece of work about the Josef Ng affair, “The Wen paper: Monday January 3 1994”. Here, Lee places side-to-side the newspaper accounts of the episode with his re-drawn version, showing the correct version of the episode and the presence of multiple narratives. In his blog titled Republic of Daydreams Lee Wen wrote extensively about Josef Ng. In one post from 2013, he recalls meeting him at the gallery in Shanghai that he was running, and giving him a line he never forgot: “tell them I am fine, I may have broken the law, but I did no wrong.”

Censorship is about a singular narrative

It might relate to history, or reverberate in the picture of Singapore the country wants to believe for itself. However you want to look at it, the idea of censorship as something conveying a singular narrative has been a constant topic in the conversations I had with artists in Singapore. Including those whose personal work was far from controversial. This singular narrative doesn’t necessarily need to involve notoriously contentious subjects; such as race or religion. It might simply involve a questioning around why certain decisions are made, around transformation of spaces, the role of memory and certain parts of the national history. “These questions, they are not provocative, but are conversations that we ought to be having about spaces, memories and narratives that we share or are vested in,” said artist duo Perception3 who are tackling precisely these subjects.

I was sitting in the Food for Thought cafe at the National Museum of Singapore with Regina De Rozario and Seah Sze Yunn, the artists of Perception3, who work with video and urban space. The duo hope that government agencies like the National Arts Council could demonstrate courage and support works that enable difficult questions or conversations to take place. “It would be a good start to embrace complex issues and to make space for work that present different, or sometimes even ‘disagreeable’, perspectives.

The artists note that much of Singapore’s official (i.e government-led) narrative of its post-independence success in tinged with a sense of fragility. “Born and raised in Singapore, we are conditioned to see our success as something that hangs in delicate balance. The positive outcome of this conditioning is perhaps to imbue some sense of personal responsibility; for citizens to not take things for granted, and to go all-in to do our bit to build upon the work of those who came before. However, the negative outcome of this conditioning is a sense of over-cautiousness – of not wanting to rock the boat; of not straying from systemic norms or even questioning how these ‘norms’ have come to be. This can have an effect on our willingness and ability to have a civil conversation about things we may disagree on.”

An example is to find in Singapore’s rich racial and cultural mix, well beyond the official ‘Chinese’, ‘Malay’, Indian’, ‘Others’ categories. They explain that on paper, and in general practice, Singaporeans are expected to demonstrate cordial respect for each other’s cultural and religious practices, “But while we are proud of our country’s ‘racial harmony’, we do wonder: how deep does this understanding and interest in each other go? Especially beyond the tropes of token representation, often expressed through food, language, costumes, etc.?”

Regina and Sze Yunn felt that in Singapore it was art to be the more progressive sector in terms of engaging in these conversations, compared to other branches of society. This is because the practice of art is largely not ‘result-oriented’, but rather, question-eliciting, and tends to welcome diverse perspectives. . This consideration came from their experience of collaboration, where Sze Yunn had a design background, and Regina an art background. “From the beginning we have realised that our approaches, the starting points, are different from these two practices,” said Sze Yunn. “From the design perspective, I’m always trying to look at the result that I want to get at. I need to define the problem and come up with a solution. Whereas from an art perspective, maybe I see a problem, and maybe I don’t know what it is yet. I’m interested to find out. Artists are thinking about the questions – questioning the things that they see and expressing these thoughts. Whereas everyone else is just trying to arrive at the most effective and most efficient solution.” When she said that, I felt in all its magnitude the strangeness of Singapore trying to apply the second approach to the first premise.

It is not about antagonism; it is about creating a breathing space.

In this situation of censorship, some players in the art arena are subtly challenging the rules. One of the topics whose taboo status is slowly losing its grip is homosexuality. Sitting at Grey Projects, I discussed this particular issue with its director and artist Jason Wee. He explained to me that it is still challenging to make an openly queer show, or a show which has a very strong either political critique and social advocacy, or explicit content. This was something Jason was actively working on at Grey Projects, having a queer show each year for the past four years.

He didn’t approach the topic with the intent of challenging the system, that upfront brash rebellion western art experienced, in regard of this thematic, in the ‘80s. More than an antagonist perspective, the idea is creating a space for a community that wants to see itself represented: “My objective is not to tell a highly normative system what to do. My objective is really to tell people who might feel excluded, “hey, look, despite the system there is still a chance to do something.” We can still create a space that will allow these kinds of images or practices that we know to found their way into visible life and circulate,” said Jason.

I thought about what, since the avant-gardes has been considered an inherent opposition between what the artists are doing and what the system is calling for. In that, I found Jason’s proposition to be the healthiest, not alimenting this vertical kind of dichotomy – namely having the state as purely interlocutor, which inherently creates a power-relationship of either refusal or complacency – but rather making it more horizontal, in the sense that you are making artists talk among themselves and the public. Indeed, Jason described it as a disinterest in entering someone else’s game: “If the state constantly calls out to me, I respond accordingly either in obedience or in opposition. Then I’m working within the terms set by the state. And the terms are set in such a way that already suggests that what I say is going to be read. But that also leaves other possible vices out of the range of possible responses, because they have not been called upon in quite the same way. So for me, the artist’s or curator’s work is about constructing a dialogue or turning away from this kind of interpellation to what is the marginal and developing another space to look immediately away and imagine the state isn’t already there. It is kind of imagining its absence, or its practical absence and then working in that.”

I lingered a bit on Jason’s way of phrasing the concept: “imagining the state is not there.” I tried to understand how this can possibly happen, in a situation where, as soon as artists finish school, the government is present straight away with his possibility and attached strings.

Jason recognized that the government intervention in the arts is a very entrenched part of the system and Singaporean life in general. This results in people drawing equivalences that the state represents society: “And that is not always the case. I think artists often get into this trap, thinking that if they just work with the state, it is really working with the public, or in the community. So it is possible to work and figure out ways of either self-organisation or to look for transnational opportunities. So exchange relationships, residencies, all these sort of things are important.”