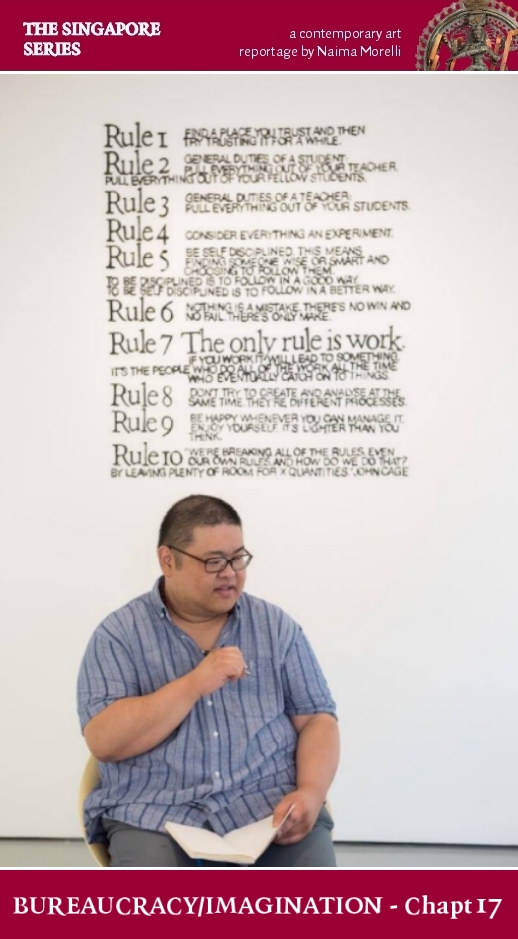

Lee Wen

I first met Lee Wen in Rome, in the courtyard of my very first house in the Eternal City. The place was in the local Chinatown, called Piazza Vittorio. This is not a nice Chinatown. It doesn’t have the fancy portal to mark its main street, nor particularly good restaurants or shops. Indeed, Piazza Vittorio become the go-to establishment for Chinese immigrants only in the late ‘80s, where they set up bare shops selling cheap clothes, where no one ever goes buy anything.

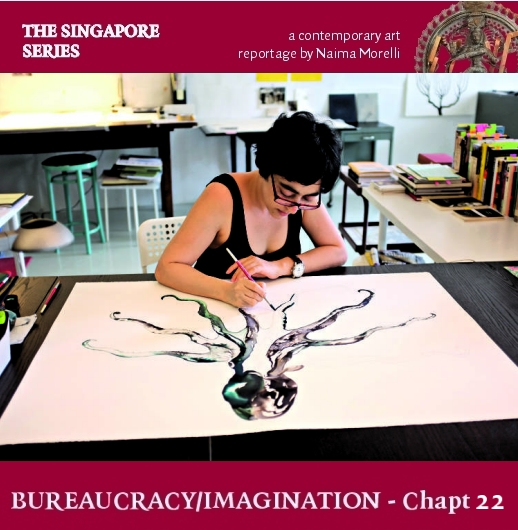

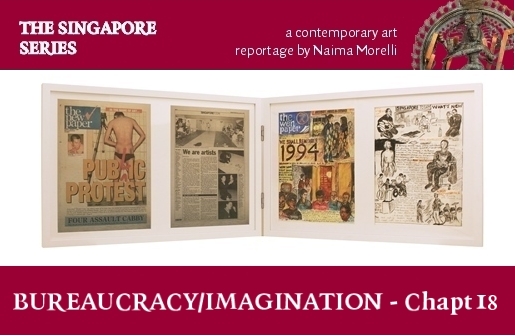

The building where I used to live in had a large courtyard that led into different buildings, and in the middle of the courtyard there was a small gallery, called La Nube di Oort. One day I got an email from the gallery saying that in a few days there would have been a performance called “Un evento piccolo ma significativo” (A Small but Significant Event), featuring artists Lee Wen, Myriam Laplante, and Mike Cooper. The press release explained that Mike Cooper would have recreated a sound performance – which he didn’t attend. His performance was a personal sonic response to a short video clip of part of English musician David Toop’s performance posted on Facebook. Lee Wen would have responded to Mike Cooper’s response and Myriam Laplante would have responded to Lee Wen’s response to Mike Cooper’s response. I thought this process of osmosis, lost in translation and enrichment in translation was quite jarring. In my mind, the artistic device was similar to the American version of Singapore which was Madripoor and my Italian perception of Madripoor. And neither myself or Claremont had ever visited Singapore at that point. The press release went on to say a bit about the artist’s bio. I knew two of the three artists. Mike Cooper was a white-bearded English singer-guitarist forever wearing Hawaiian shirts and a straw hat even in winter. He rose to prominence by innovating the international scene with the explorations of avant-garde sound. Myriam Laplante was a Canadian artist who moved to Italy a while ago. Her work, consisting of performances, installations, sculptures, photographs, and drawings never lacked in dark humour and was heavily parodist, absurd, cynical, sad and disturbing. Being a vernissage-hopper I happened to have seen Cooper and LaPlante in action a few times already. But I had never met Lee Wen. I knew him for being a pioneer of performance art in Singapore since the ‘90s. The press release informed me that his multidisciplinary work, spanning from writing to song, was a constant reflection on society, motivated by strong idealism and a revolutionary impetus.

Read More