THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 32

Donna Ong

Part of the charm of the forest is that it is supposed to be dangerous and mysterious. In this way you can still appreciate it but in a safe way. It’s an interesting metaphor about what is happening in Singapore. In the first chapter we have already talked about the work of Donna Ong in respect to the idea of tropical nature. We looked at “The Forest Speaks Back” which explored the idea of the tropics, by conveying two different points of view: that of the colonisers, and those of natives. Donna is interested in how the narrative for nature in Singapore has changed and evolved: “I think previously there was a lot of emphasis on the Garden City, so we had tropical nature but made it into a garden. A tamed tropical garden rather than a forest.”

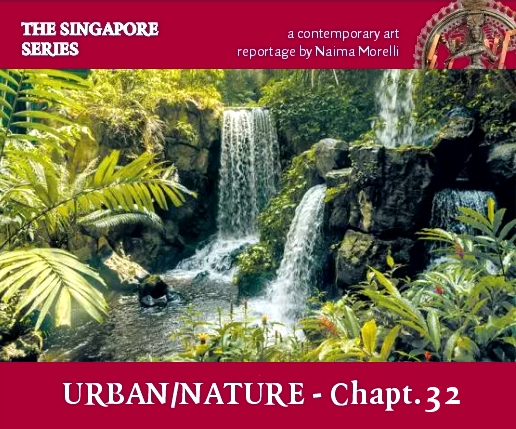

“Recently the forest seems to be like a zeitgeist thing,” she said. “Everyone is talking about forests; everyone wants a forest in their development. I have been taking pictures of artificial forests and I was shocked to see how many places in Singapore have an artificial forest. There is a hospital here called Khoo Teck Puat, that has a forest with a waterfall at its very centre.”

The artist explained to me that the forest trend is pretty substantial, and that different places like Singapore Flyer, have their own forest in the centre. “It’s less of a garden and more like a tropical wonderland — similar to a walk through the forest but a very clean and neat one.”

Photographing these landscapes, the artist was shocked to see how some of them looked totally natural. One time, she decided to meet with her photographer for a project to photograph two big waterfalls at sunrise. “When he got there he called me and said, guess what? The waterfalls are not on! They switched off the waterfall, they only switch them on at 8am. They looked so natural to me that I imagined they would be flowing all the time! The concept of a tap for a waterfall just blows my mind!” said the artist with a laugh.

I tell the artist that the reason why it is so surprising is because for us nature is supposed to be, well, natural. It is in the root of the word itself. But artificial forests are only about the beauty of the forest, devoid of its function — at least partially. The forest becomes only an image, a façade. In this perspective, gardens are not natural either. Donna Ong notes that this distant image of the garden exists because for Singaporeans, seasonal gardens are something that you don’t experience in the everyday: “Flowering plants that change throughout the seasons are actually what we have learned from books.” She compares it is with Western art history, which most Singaporeans don’t experience firsthand and don’t grow up surrounded by, until they start travelling.

She noted that for example in “And We Were Like Those Who Dream”, which was exhibited in Primae Noctis gallery in Lugano, she got a different response from the audience, who are used to seeing the art historical works in person: “The reaction was ‘ah, it’s in this church, it’s in that church.’ For us living in Asia, there is no hierarchy in terms of “foreign” images whether they are from Western Art History of botany. The flowers are all from books and you haven’t seen them in real life — it’s just an image to you. For me, I find that naivety and freedom from accuracy and history really interesting. I wanted to make a space where the plants are from different scales and from different seasons but yet put together, they look like a garden. They shouldn’t be in the same picture, and yet in my work, they are. It’s kind of how I imagined the garden when I was young, coming from a place where I don’t know the plants and had never experienced the four seasons.”

She said that when she would go to England, her friends would go on these walks with their parents and they would actually point out the plants and name the plants: “You know when they see my work, they actually recognise the plants and they associate them with the season, they associate each plant with certain areas in England. But for me, when I see this, it is just a flower that I saw in a book. I was more interested in the way all these plants are isolated and placed in different pages of a book. It made me just want to put it all back into nature, into the garden. In my work, the garden goes through different seasons, but the plant choice is not based on their seasonal availability but on colour.”

For you it’s just a tone, not ordered and functioning in a botanical sense, with a sort natural truth. You are somehow creating your own artificial gardens where the image is stronger than the function. They are impossible gardens. It’s also interesting what you said about how different people can read different things in your work, depending on the context…

Yeah and even the idea of Mary. I understand the context in terms of religion and art history. She’s the most painted character ever, right? For me she’s the perfect character, she represents a woman associated with the garden and she ages in different paintinngs, so there is this idea of time. But when I showed my work featuring Mary in Italy, I got very mixed reactions where people wondered why I used images associated with Western art history rather than my own culture, which they perceived to be Chinese art history. However, although we have a very rich traditional Asian culture, Singapore is in a strange place. It is a very young country where when I was studying art, artists didn’t learn traditional Asian painting techniques or history. We were taught instead, Western Art history and contemporary art. So that became more familiar to me than my own cultural background.

I was wondering, if art history is taught in this way, do you still feel a sense of ownership for a certain segment of art history?

I think Art Histpry always feels strange to us. We don’t even know how to pronounce the names of some otf these artists because their names are in languages we have never even learnt or heard. Every artist has the same knowledge, but it’s different because we learnt it from mediated secondary sources and don’t see the real works until later in life if we get the chance to travel. This creates situations where we know the works but not their contexts and are thus not sensitive to their religious and historical contexts. In another work of mine, I placed the angel in a diorama above the diorama of Mary. I was told later that some Catholics who saw the work were offended with my placement because Mary is supposed to be on top, not the angel. I am Protestant, but I didn’t know anything about these pictorial traditions. In my mind, angels are from heaven, so they were placed above. I only encountered such images in books, not in the context of the church and didn’t realise they could cause such controversy.

Can you tell me about the concept of your show at Fost Gallery in Singapore, which is called “My Forest has no Name”?

“My Forest has no Name” is about naming and claiming nature. For example, the Amazon’s name comes from Greek classics. They talk about these warrior women that were fighting alongside men. One French guy who was there and wrote about it was reminded of the myth. So he called the place Amazon. You name it, and by naming it you feel like you have the right to own it or claim it, exploit it.

And also superimpose a different narrative which wasn’t the one conceived by the local population.

Exactly. I was also interested in how the forest is described in the past (e.g.17th and 18th century) and how much of this idealistic aesthetic has been transferred to us in our modern-day fake forests. These images are so persistent and unrealistic. Living in the tropics, we see and experience real forests, yet we still choose to perpetuate these idealistic images in our landscapes and art. In my work, I explore possible reasons for that. Are there any hidden advantages, or are we doing it naively? Malaysia recently had this grand plan to build an island city off the coast of Malaysia called the Forest City. It will be very close to the sea boundary of Singapore and there are plans to construct first class homes, shopping complexes and schools there. Such projects reinforce my belief that the idea of the forest is very current, very zeitgeist. A lot of people and places are picking up on the forest theme and so it’s a great time to reflect about the meaning behind it and its significance.